Proscenium Is Key To One Of The Largest Coordinated Suburban Retrofit Endeavors In U.S.

- August 22, 2023

Article originally published in Public Square, A CNU Journal

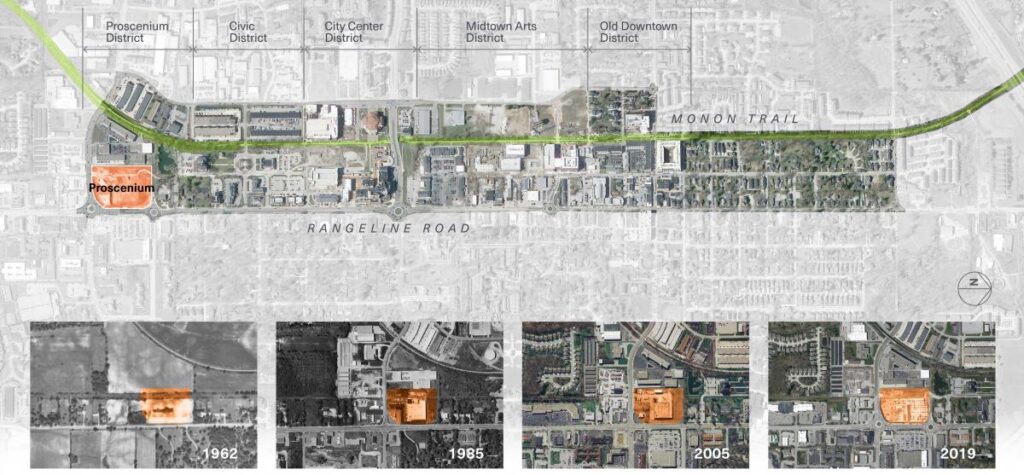

The Indianapolis suburb of Carmel, Indiana, is creating a downtown on a 1.5-mile-long corridor that includes a wide range of development types and public spaces, reform of streets, and a unique rails-to-trails project. From a 21st Century planning and development point of view, it is one of the most interesting suburbs this side of the Atlantic.

“Carmel has dedicated the past 25 years to reinventing itself from the archetypal suburb to a New Urbanist City,” notes Woolpert, the multidisciplinary architectural firm that designed The Proscenium, a key recent project.

Proscenium anchors the south end of the downtown corridor and the five urban districts are adjacent to one another, top. The site over time changed from rural to suburban, and finally urban redevelopment. Source: Woolpert.

The Proscenium contains 226 living spaces (all market rate), 85,000 square feet of corporate offices, and 25,000 square feet of retail, restaurants, and small offices. The development is 7 acres, including six blocks and a grassy green—sitting at the top of a parking podium. Novo Development Group built the $60 million project in coordination with the Carmel Redevelopment Commission (CRC), on the site of an underutilized brownfield. The project used tax-increment financing, a tool that helped to build Carmel’s downtown.

Proscenium site plan. Source: Woolpert

Whereas some suburban retrofits are isolated, the many connected projects in Carmel means that The Proscenium is part of a much larger urban whole. The project is not an urban island, but “rather a continuous integration into a bustling and evolving fabric,” according to the design team. The Proscenium means the front of the stage, and the name is a metaphor for living at center stage, notes Tim Hill, who is the project manager for Novo. That’s a bold statement.

The planning is geared to people on foot and the project is intentionally “all sided,” whereby all building faces are designed with the pedestrian in mind. “Whether enjoying a community event on the green or strolling from your front door to a restaurant, one experiences everywhere the result of prioritizing pedestrians over cars.”

The large existing block was divided into small city blocks, increasing connectivity to adjacent parcels. The below grade parking enabled the creation of authentic pedestrian spaces, while providing intuitive vehicle access and wayfinding for first-time visitors. Included in the block structure is a long, north-south pedestrian promenade and a green—two fine public spaces.

The architecture of the buildings is designed with active, interesting frontages for pedestrians. “Each of the project’s five residential buildings directly engages the street through either residential front doors, stoops, or ground-level uses such as office, retail, and dining.”

The Proscenium is across the street from a grocery store and a short walk from government services, arts and recreational venues, other retail and civic buildings, and a wide range of public spaces. “Immediately to the west, the Monon Trail provides a nationally recognized rails-to-trails link that extends through Carmel to downtown Indianapolis.” The project has no affordable housing, although there are subsidized units being built near downtown.

Nearly all of the 490 parking spaces were placed below grade. To reduce of the high cost of the underground structure, shared parking was utilized to the greatest degree possible. The streets were placed at the level of Rangeline Road, the adjacent thoroughfare.

Carmel is known as the “roundabout city” (more than 140 have been built), and several of these small circles are located nearby to calm traffic, including two adjacent to the site on Rangeline Road, where a road diet was implemented. “Immediately to the west, the Monon Trail provides a nationally recognized rails-to-trails link that extends through Carmel to downtown Indianapolis.”

“We are thrilled to see our investment into what was once an underperforming property is now producing results in the way of private investment and new jobs for Carmel,” according to Jim Brainard, mayor of Carmel.

In before and after aerial photographs, the transformation from low-slung suburban fabric is apparent. Source: Woolpert.